With jobs on the line, why are Market Basket employees so loyal to Artie T?

With each passing day, New England waits for a smoke signal that the Market Basket board has reached an ownership agreement for their 71-store grocery chain. The latest comes from Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, who said Wednesday that he’d spoken with the chair of the Market Basket board, Keith O. Cowan, and former CEO Arthur T. Demoulas, and that a deal on the sale price was close. He urged striking employees to return to work during the negotiations.

Earlier this week, Market Basket issued another ultimatum to their striking workers. Return to work by Friday, they wrote Tuesday to some 200 employees, or you’ll lose your jobs.

After nearly a month of strikes uniting aproned deli clerks and suit-jacketed managers, many deliveries, especially of perishable items, have stopped. What’s left on the shelves — gluten free products, for example — isn’t moving because the chain’s loyal customers, carb and non-carb eaters alike, aren’t crossing the picket lines; in many cases, they’ve joined them. The store has lost up to $10 million a day.

Entire aisles remain empty at this Market Basket store in Tewksbury, Mass. NewsHour still photo.

Workers are feeling the pinch. Market Basket has cut the hours of thousands of part-time staff, many of whom are now applying for unemployment benefits. And Market Basket started holding job fairs last week to internally replace striking managers. But those fairs, too, were picketed.

So will the ultimatum shut down the protests?

Fifty-five-year old Chris Elkins, who supervises the courtesy booths at the chain’s 71 stores, told the Boston Globe she’s nervous. “I’m a widow. I have one income, and I haven’t gotten paid in four weeks.” But she didn’t think the board would actually act on its threat.

The board very well could act on the threat, said management consultant and worker ownership advocate Christopher Mackin, but “following through may well backfire and deepen customer antagonism toward the existing management group,” he told Making Sen$e Wednesday.

The latest ultimatum seems to have emboldened some strikers. “If anything, it strengthens our resolve to bring Artie back,” Anne Browne, 23, of Market Basket’s IT department, told the Boston Globe.

Since the Market Basket board ousted CEO Arthur T. Demoulas in late June, thousands of the chain’s 25,000 employees have walked off the job in support of their former boss. In his place, the board, which is controlled by Demoulas’ cousin, Arthur S. Demoulas, appointed two new CEOs.

Artie T.’s their Greek God, receding hairline and all — a ubiquitous symbol of the labor struggle that has enthralled New England, and increasingly, the nation.This isn’t the company’s first plea to get workers back to their posts. When more than 2,000 employees rallied outside company headquarters in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, in late July, the new chief executives threatened that employees skipping work would lose their jobs.

For eight of the protest ringleaders that threat had teeth; Market Basket fired them. But that didn’t stop a second rally three days later, and ever since, employees and boycotting customers have decamped to store parking lots, chanting, “Bring back Artie T.”

From Tewksbury all the way up to Biddeford, Maine, Artie T. is everywhere. His head bobs above the crowds as protesters thrust homemade placards into the air. He’s their Greek God, receding hairline and all — a ubiquitous symbol of the labor struggle that has enthralled New England, and increasingly, the nation.

Employees and customers hold a rally in support of Arthur T. Demoulas and Market Basket. Photo by Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty Images.

This labor strike is attracting widespread attention because it’s not a labor strike in the traditional sense. Market Basket employees don’t belong to a union, and white collar managers are striking alongside the blue collar workers they supervise, rallying for Artie T.’s return.

For all the heartwarming stories about employer and customer loyalty, however, Holman Jenkins Jr. questioned in the Wall Street Journal last week just what that loyalty will get the employees.

Arthur T., his family opponents might say, had every incentive to behave in ways that inveigled employees to his side. He had every incentive to keep costs inside the company and shift profits outside to related parties, where 50.5% wouldn’t go to relatives he detested.

Because, Holman predicted in the same piece, any resolution “is likely to lead to Market Basket being run more leanly and meanly to pay down debt incurred in buying it,” those striking workers, he continued, “might have found their leverage greater if they had rolled with the change in control from Arthur T. to Arthur S. rather than forcing a crisis that ends with the company being sold and worked to satisfy debt holders.”

Artie T. has defended the fired employees and submitted an offer to buy the 50.5 percent of the company shares controlled by his rival cousin. Last week, he rejected a deal from three Market Basket directors that would have allowed him and the striking workers to return to the store to get it back on its feet while the board continued to consider his purchase offer. Arthur T.’s spokesperson dismissed the proposal as “an attempt to have [Arthur T.] stabilize the company, while they consider selling it to another bidder,” according to the Boston Globe.

Delhaize Group SA, the parent company of Hannaford’s, another New England grocery chain, has submitted a bid, likely for only the 50.5 percent Arthur S. controls, but no one knows for how much money.

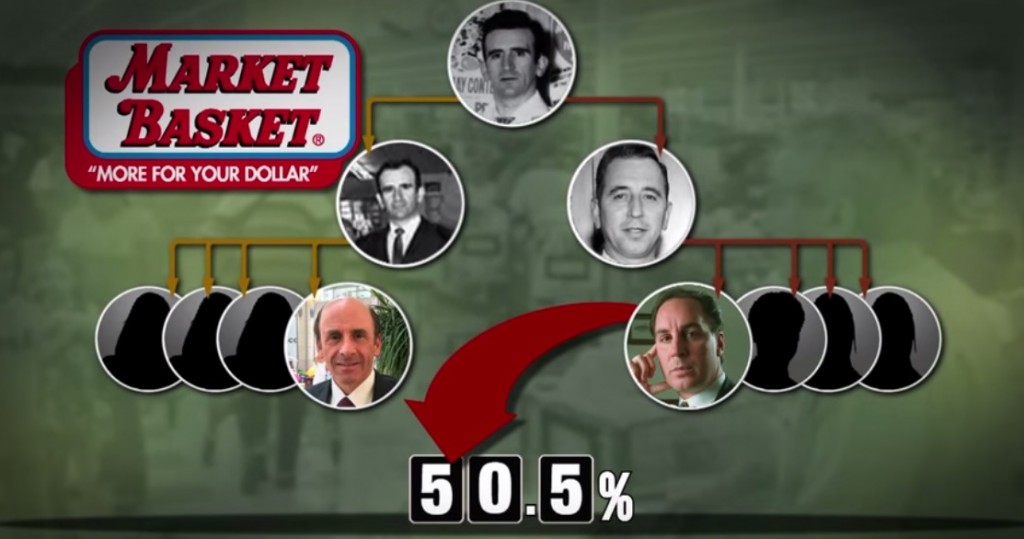

The two main warriors in the ownership war remain the family factions. Five of the company’s nine shareholders support Arthur S., who controls the shares of two of his sisters and of the widow and daughter of his deceased brother. The four remaining shareholders — Arthur T. and three other sisters — control 49.5 percent of the company.

The Arthur S. Demoulas side of the family, right, owns 50.5 percent of the company. NewsHour image.

On Sunday, Arthur T. blamed “onerous” terms from his cousin’s faction for blocking any progress on the sale negotiations. But what those terms are, as well as the price of Arthur T.’s bid, remains a mystery.

So how long can negotiations to resolve the family feud take, and how long can the workers, many of whom have lost working hours and used up sick days and vacation time to strike, continue their fight?

Part of the answer to the latter question, at least, is that this is a family struggle in more ways than one. Protesters aren’t just resisting the ouster of Market Basket’s CEO; to them, Artie T. is “our” CEO. In Massachusetts’ northern suburbs, the filial piety has become synonymous with the store itself. “We’re in the grocery business second; the people business first,” protestors chant.

Protesters at a Market Basket rally hold a sign saying “One Family,” featuring giraffes, the mascot they’ve adopted. NewsHour still image.

For outside observers, though, it’s hard to imagine this refrain justifying workers risking their jobs for their boss. But to them, Artie T.’s not just some mythical hero. The stories abound; Artie T. cares, protesters say, not just about “his employees” in the abstract, but about individuals like Mary Jane.

Mary Jane Findeisen is an officer manager at store number 10 in Methuen, Massachusetts. Arthur T. visited her husband when he was dying in the hospital, and as she recounts below, he spent 45 minutes comforting her and thanking them both for their service to the company. “It means the world to me, so this is why I’m here,” she says.

How could a company, and one man specifically, be so beloved? From Arthur T.’s personal touch — the phone calls to workers and his attendance at their relatives’ funeral services — to the company’s profit-sharing system, employee scholarship program and generous wages (starting salaries for full-time clerks are $4 higher than Massachusetts’ minimum wage), it’s not hard to see why employees have been loyal to management under his leadership.

In today’s corporate world, John A. Davis wrote on the Harvard Business Review’s blog, we’ve forgotten about the virtues of family-owned companies. They’re “a largely silent sector of market capitalism,” he writes, which represents two-thirds of businesses throughout the world and half of U.S. companies. He also points to studies showing that public and privately held family companies tend to perform better. “They are stronger financially, have higher stakeholder loyalty, live longer, and are more trusted by the public,” Davis wrote.

NewsHour still image.

From a balance sheet perspective, though, how does Market Basket offer both higher-than-average salaries and charge lower-than-average prices? Christopher Mackin pointed to several factors. First, the company, unlike some competitors, maintains a very low level of debt on their balance sheet, which allows it to accumulate cash reserves. And second, Market Basket makes money in a low-profit-margin business because of a high sales volume. (Mackin notes that they’ve grown steadily, opening new chains throughout the last decade.) That volume is sustained by the intertwined forces of employee and customer loyalty. The fact that Market Basket prioritizes employee loyalty, Forrester Research Inc. analyst Emily Collins told Bloomberg, has inspired customers like her to boycott their local stores.

Whether that loyalty will be enough to patch the holes in workers’ paychecks, however, is another matter — especially if there’s any credibility to the board’s latest threats, and they actually do fire people come Friday. MIT’s Tom Kochan, co-director of the Institute of Work and Employment Research at the Sloan School of Management, suspect it’s a mostly empty threat, but that may not be enough reassurance for workers who find their livelihoods on the line.

In the meantime, New England waits. At the very least, Kochan pointed out, there hasn’t been a press release from either Demoulas side in a day — an optimistic sign, he said, that maybe they’re busy getting down to work on a deal.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eelsGqu81orqKsmGK3sK7SZqanZaSdsm64yKecZq%2BYrnqivsRmpJqqm5rBbq7ArKKerF2aurG4zrKcnqtdqLxuuM6ymKVlpKR6or7TopxmrA%3D%3D